If you’re new to my newsletter, you can read a bit more about me, the work I do, and why I write here.

This week I drove to Greensboro to record an interview with Anne Helen Peterson for an audiobook/podcast that’ll accompany her book on burnout. (Anne also has the world’s most popular free substack newsletter and for good reason. Go subscribe!). Due to some technical difficulties we couldn’t record this week and will get to it next week.

This is the studio I was supposed to record in.

Preparing to record has proven helpful in thinking through my experience of burnout over the last year or so.

I wrote last week about how I’m now about four months removed from burning out of a church. I lived with the “baseline temperature” of stress and anxiety for a year and most acutely for six months. Last week I wrote, “that I simply had values and convictions that were too strongly at odds with too many in the congregation.” I’ve talked with a number of other people experiencing burnout in their professions and have tried to pay particular attention to teachers, social workers, other ministers, and those in non-profits. These types of work often involve people’s strongly held values and convictions. For this reason, people working in them have a harder timeless compartmentalizing. Burnout, as I understand, results not just from working too much but from the kind of work we do.

The more I’ve thought about it and as I’ve talked it over with friends, I realized that while conflicts over values play a role, the power structures of an organization and institution also play a significant role. Whose values win out in an organization matters especially when people’s values conflict sharply and irreconcilably.

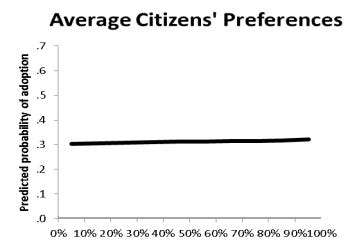

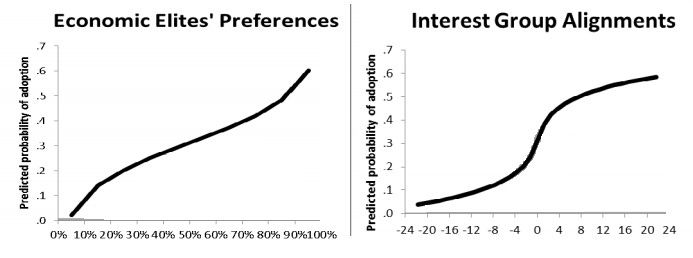

This week I re-read this summary of a report about the degree to which wealthy people influence policy in America. As support for a policy grows amongst average citizens, that policy stands basically no greater chance of being enacted by politicians in power. When 0% of the average citizens support a policy it has the same probability of enactment as when 100% of them do.

But once support for the policy grows amongst the economic elite, its probability of passage goes up. Everyone knows that politics works this way in America work.

Now let me tell you a secret every pastor knows but will rarely tell others: pretty much exactly the same thing happens in our churches. We all know this. We all talk to each other about it. All our denominational leaders know it. Every congregation and non-profit of which I’ve worked for or participated in has had to shape what they do to ensure the support of wealthy donors and congregants. Sometimes we do this consciously, but most of the time it just serves as the baseline assumption from which we operate.

How does this work? Do pastors and non-profit leaders sit down and go “Okay. What do the rich people want?” Not really. Usually they ask, “What can I do to ensure the financial viability of this institution?”

They don’t necessarily cater directly to the values, desires, and convictions of those that help pay the bills. Instead they leave projects, theologies, ministries, and convictions off the table that they think the wealthy members will disagree with. It’s not about making sure you cater to their values. It’s like jazz: it’s the convictions and values you don’t say.

What does this look like and how does it lead to burnout?

At my previous church, I read a book called Unified We Are A Force with some of the twenty and thirty year olds. The book’s authors write about churches and the power of working people when they form unions. I read it with this group because in the course of our conversations, they raised concerns about their workplaces and the anxieties that go along with overwork and burning out. I ran a small description of the book in the church bulletin a few weeks prior to the group starting. A very small number of older, wealthier church members saw that announcement, got copies of the book, read it and got upset. They claimed that because the authors held theological beliefs they disagreed with that a minister from their church shouldn’t read it with church members. I represented the congregation after all. Another said that unions lead to socialism and that leads to communism and that reading this book gave grounds for my resignation. This gave rise to inevitable tension. I struggled to minister to people that didn’t want me to have my job and and made sure that I knew that.

In the midst of this dust-up, I had lunch with an influential church member a few of them had alerted to their concern. They threatened to leave the church over it, and he sought to intervene. At one point in our conversation he said “Well it’s just a good thing that X isn’t upset. Then we’d really be in trouble.” X was one of the wealthiest members of the church, but the book didn’t bother him. In that moment, the member I had lunch with seemed to recognize that he’d tripped up and basically admitted that we needed to keep X happy so he’d keep giving money. I could tell he knew how . He tried to backtrack. “Well. I mean, not that that’s how we do things, but you know what I mean.” I did.

At this point I should say that this church and and this dynamic don’t stand out in this regard. American churches have done this for centuries. Non-profits have done it for just as long. We have to live with the weight of that history. The straight line and the one going up and to the right above are as American as apple pie. Everyone knows rich people run things. Every pastor knows this. Every average church member knows this. In my experience both in and outside churches, the only ones that don’t see the ways that everyone bends themselves to the whims of the wealthy are the wealthy themselves. You can see it in Betsy Devos’s shock that people don’t like her or her plans to turn every public school into an online charter or Howard Schultz when a pundit confronts him with how income bifurcates America. They’ve gone at least two decades without another human being they couldn’t immediately fire looking them in the eye and telling them something they didn’t want to hear. While this situation may lack novelty, with inequality growing, congregations shrinking and aging, budgets declining, and people polarizing, all of it feels so acute. The margin for error, the breathing room feels gone.

Many within the church considered these complaints ridiculous (an overwhelming majority of the people aware of them). However, some in leadership thought of a simple solution: read the book with the younger adults, sure, just don’t print the announcement in the bulletin or put it on the website. They suggested we avoid the conflict all together. Hide the stuff people disagree with under the rug. I once had another church member describe some of the disgruntled people as “landmines” and he told me “you’ll run into landmines in any job. You’ve just go to figure out how to avoid them.” This advice troubled me because calling people “landmines” deeply dehumanizes them. I don’t want to look at other people, human beings capable of aspiring to do better and the agency to potentially get there, as objects to tiptoe around.

Looking back on it now, I can see the way this lead to burnout. It’s not an outright betrayal of one’s values, it’s just concealing them out of fear of how those with the power of money will react. Every pastor knows they can’t say everything they actually think and believe because doing so would compromise their standing with members in the congregation. Pastors take this as a bedrock axiom of doing ministry and working in non-profits, but no one talks about just how draining it is. We either don’t say what we truly believe, don’t act confidently according to our understanding of the faith and calling to leadership, or we coat the whole thing in so much unclarifable unclarity that no one can actually disagree with what we say. Either way we end up doing a whole lot of work to make sure people don’t use their power over us.

I caught up with a friend of mine that burned out of her church a few months before I did. We talked about her experience and she said “Oh absolutely. I had to dance around many of my thoughts on God, politics, gender, and especially sexuality. Eventually you get tired of dancing.”

The whole situation drained me because I felt that by holding back the truth from those congregants, the truth about a book or about my convictions about the virtues of democratic socialism over capitalism, I betrayed not just myself, but them. I came to believe that this avoidance should cause me to question whether I ought to work as their minister. I believed I had an obligation of some kind to these people, but their wealth and the power it afforded them scared me. It scared me because of the the entire history of a hundred years of 99% of churches structuring themselves around protecting the rich from hearing they’re wrong, that sometimes their ideas don’t benefit the larger community. I got scared because somewhere along the way so many churches became one more place for society’s most comfortable to get just a little more comfort. I got scared because at some point you can’t serve both God and money, and that’s true not just of our own money, but other people’s.

I think about this quote from Merve Emre all the time: What is true for human relationships is true for art and politics. If I care about building a world, real or imaginary, with you or for you, then I should think about that world in the most accurate and realistic terms possible. I should hold you to the same standards of precision that I hold myself; even—and especially—if we disagree; even—and especially—if that disagreement is uncomfortable and alienating.

If perfect love means the eradication of fear, a sure sign of loving someone is that you’re not scared of them, no matter how much money they have. That you love them enough to accurately describe the world you hope to build with them. I did hope to build a world with them, but it wasn’t the world they wanted. I was okay with all that, but to have to leave the accuracy and realism of the world I hoped to build with most of the church off the table, to leave its values unspoken for, felt like a real betrayal of that world and the ones I thought God wanted us to build it for.

You can subscribe to this newsletter HERE.

Things I read this week that I liked: