Christians and the Workplace

Why you can't explain what's happening in church right now without capitalism

I normally write this on Sunday evenings as a way to unwind from the week and give me something to think about besides all the work I have on Monday morning. This last week I led a workshop on “Christians and the Workplace” at the national gathering of the With Collective. Below is what I shared with the group there.

Workshop Description: The past decade has seen an explosion of books on Christians in the workplace. Rarely, though, do such books address what actually makes a “workplace” and often take for granted that our congregants live and work within a capitalist system. This system, by its nature, produces problems in the workplace and in our congregations, problems like income inequality and instability, poverty, and insurmountable debt. Come hear John Thornton Jr. share about how his church Jubilee Baptist has oriented their ministries to address these problems while also sending congregants into their workplaces to transform them in the name of God’s liberation.

At the moment, it appears to me that a lot of us in ministry find ourselves trying to solve a constellation of seemingly unrelated problems. We have to deal with dwindling attendance as people don’t go to church with the same frequency they once did or just stop going altogether. Members’ packed schedules leaves them less time for church. A lot of us would like to know what to do about poverty and homelessness as our cities rapidly gentrify. I imagine your city is a lot like mine: million dollar condos and people sleeping on the street. Without you telling me where you come from, I can probably bet that you have school districts made up of mostly white, affluent students that get a far better education than their poor, minority peers in other districts. For a lot of us this represents a failure of the church to work towards social justice for all people. Those are some of the main problems I’ve had to deal with in ministry in my relatively new career. We could add stretched budgets or polarized politics and/or theology. Racial reconciliation or the acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people.

Now, I know this might feel like a strange setup to a workshop on a “theology of the workplace,” and I actually want to table those problems for now, but I think it’s important that you keep in mind they are related to our theology of the workplace and I’ll definitely return to them.

Most of the time I find theology about the workplace dreadfully boring. Discover your vocation, follow your passion, root your work in loving your neighbor, don’t put profits over people etc. I recently read a few books on work and vocation preparing for this and all of them have this timeless-truths-we-just-need-to-remember quality. Just remember your vocation. Use the power you have as a CEO or an elected official for good by raising your worker’s wages a bit or making sure minorities are protected. Go to your job and do it with excellence as if you do it for God. Not a whole lot to argue with there.

I recently read a book on “the common good,” that said that the problem with people leaving the church was our culture’s selfishness and the church’s lust for power. Okay? That seems like it’s just always true. It strikes me as weird that so many people just decided to act more selfishly recently even as the author traces the causes back to existential philosophy.

The solution then is to recall our vocations, recover our roots, not move away from family, reframe work as good and sacramental. Sounds good enough.

Here’s the thing about timeless truths: they’re always true and rarely useful. That’s kind of how I feel about a lot of theology and work stuff right now: it’s not very useful. It just doesn’t explain much. Is the problem really that we’ve grown to consumeristic or individualistic? And if so, what explains that drift other than general human sinfulness? But sinfulness, like redemption and resurrection, happens in history. We don’t sin in general just like we don’t practice grace in general. What’s historically significant about how we live and work now?

Here’s the question I don’t see a lot of Christians asking right now: what the hell is capitalism? What is capitalism? Why is it distinctive from other economic models and why does it matter for the workplace and then why does that matter for our churches? We all agree that we live in an economic process and system called capitalism but why don’t we talk about what it is, how it works, and why individualism, consumerism, inequality, the loss of common good result from it rather than cause it?

At my church we teach a financial literacy class. We think that people should understand their relationship to work and finances. Our class, however, differs greatly from a Dave Ramsey Financial Peace University class. Karl Marx serves as our main guide and each week we read about 5-8 pages of his book Capital and discuss what he says. Capitalism has no shortage of cheerleaders so we think maybe we should also take time to listen to one of its foremost critics and see if what he has to say about capitalism actually makes some sense. If it’s true then we don’t have to hide from it, and it would help us understand the problems we deal with in ways other explanations don’t.

Think for a minute about what would happen if you just stopped showing up for your job. The first day, your boss might call to check on you or like most workers in America, they’d just fire you. So after some time missing work you run out of vacation days and then you lose your job. Okay so now you lost your job, but you still have to pay rent or your mortgage. You still have to pay for food for you and your family. You still have to pay off your student loans and that medical debt and those credit cards. And so now you’ve got to find a new job because you don’t have any communal land to fall back on and work to grow your own food or build your own shelter. You have to get a job to survive.

And what’s a job? Well it’s a thing where you say to someone, “I’ll show up and do what you tell me to for a set amount of time if you give me a set amount of money.” They can hire you because they (or likely someone much higher up than them) owns a bunch of stuff, and needs someone to work with it to make it valuable. An agricultural capitalist owns land and seeds and a tractor, but needs to hire someone to actually turn them into food. Someone that owns a construction company owns a bunch of steel, concrete, power tools, and yellow vests, but needs some people to actually put the vests on and to produce a house that the capitalist can sell to someone that wants to buy it.

Here’s what makes capitalism as a system so distinct from previous systems or alternatives: work, the workplace. That situation I described, where you have to earn a wage to just to survive, means you have to do something very unique in human history: you have to sell your time as a commodity to someone that owns all the stuff needed to make things. More often than not, you don’t produce something on your own and then go sell it. Someone pays you to produce something, a chair, an ear of corn, a feeling of customer satisfaction. You make a bunch of those over the period of time you’re paid for and then you go home and your employer gets to keep the thing and sell it for more than what they paid you to make it plus the stuff you needed to make it.

Let’s put it really simply. An investor owns a bunch of stuff he bought (supplies and machinery) and he paid 20 for it. He then pays you 10 to use the stuff to make a Thing. You go home with 10 and he keeps the thing Thing. He then turns around and sells the Thing for 40 and gets to keep 20 for himself. Why? He didn’t work on it. He just owned the stuff and had enough power over you because you needed 10 just to get by for the day. You might say that the investor worked hard to get the money to buy the stuff and to hire you. Maybe. Maybe he just inherited it in which case he definitely doesn’t do any work in this whole thing.

So now you’ve got this process going. Workers sell their time working to the owner in exchange for some percentage of what the stuff they make is worth. Marx calls these distinctions “classes” and what makes capitalism unique is a “working class” that ultimately owns nothing but their ability to work and has to sell that to a “capitalist class” that owns a bunch of stuff and buys the working classes ability to work for them.

I realize this is all really simplistic and I’m not doing all the math that Marx does or talking about the M-C-M circuit or the working day or whatever. I’m not well versed enough in this stuff to really spell it all out . But what I want you to get is that this is a fundamental, and historically unique way of working and it’s everywhere. It’s what makes capitalism capitalism and not something else.

And here’s the big thing: because of the system and the need to make more and more profit, in order to drive their competitors out of business, in order to get more money to invest and create new businesses, capitalists have to try to pay workers as little as possible for as much time as possible. It’s because of this relationship, around work, one side paying for it the other one having to sell it, that the capitalist will always make more money. And because workers totally depend on the money they make from owners they’re both going to be constantly locked into a battle for bigger shares of the profits. Maybe it’s by going on strike together or asking for a raise because of performance metrics. They’ll always try to get more of the profit from their labor.

And because of the system, no matter how altruistic they might be or how many books they read on the common good or vocation, matter how much they might want to be generous, when push comes to shove the capitalist will try cut wages or demand more work for the same pay to increase profit. They have to because their competitor might do the same and drive them out of the market. The name for this back and forth is “class struggle” and it’s inherent to the process of capitalism.

Okay so that was a lot, and of course it’s far more complicated than that. And now you’re probably thinking, “Okay, but what does any of this have to do with ministry? I thought we were talking about people leaving church or poverty and homelessness.” The answer is just about everything. Let’s take a look at our problems and see if this dynamic helps explain them.

In every church I’ve worked in the big question everyone seems to ask is “How do we get young people (millennials) to come to church?” There are a lot of answers to this question and everyone probably has a different one. The music felt stodgy, the oppressive theology, irrelevant messages, their identity was shamed and harmfully attacked.

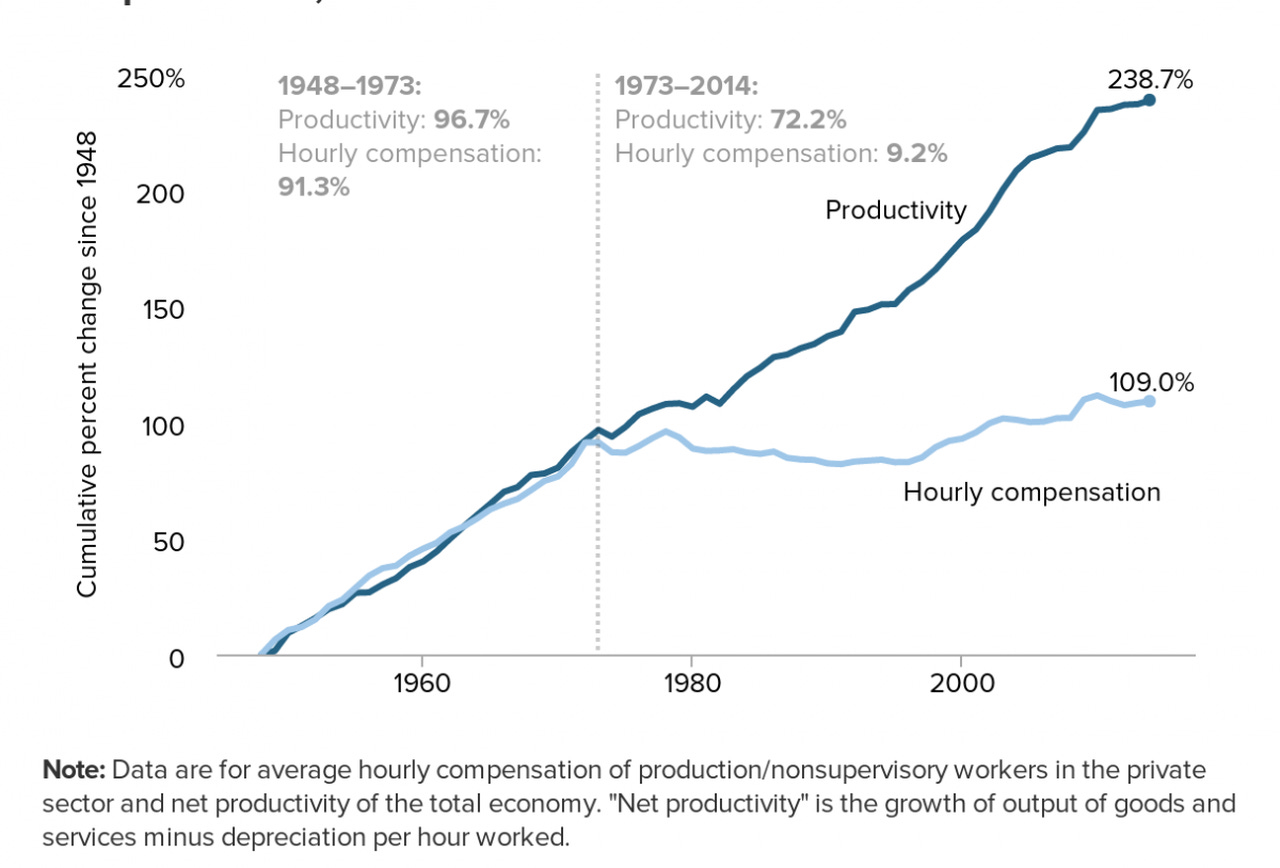

Take a look at this chart.

Notice anything that happens about 1973? Productivity keeps going up and hourly wages plateau. Remember our story of the capitalists versus the workers? Because of the nature of the system, they’re always trying to up productivity and lower wages because they make the most profit by lowering wages. And in 1973 they started doing this really, really well. And in 1980 you have the birth of the first millennials. The entire time we’ve grown up workers have been getting it handed to them in the class struggle.

Why don’t millennials show up to church? Church takes time, energy, and attention. It takes stability and commitment. It takes work. That chart above translates into massive student debt. It translates into people moving constantly looking for a better job that can pay just a bit more. It means losing a job because a ton of people will take it for lower wages. It means more of a paycheck (and consequently time, energy, and attention) going to health insurance or rent. It’s burnout.

I can’t recommend the books The Great Risk Shift or The Financial Diaries enough. They look at the fact that while income inequality has risen in the last 30 years, it hasn’t risen as fast as income instability. Why does it feel like people have less time to commit to church or family or the “common good”? It’s because they’re losing the class struggle.

The working class is losing the class struggle and for a couple of generations of churches in both their practical and theological habits, they assumed that the working class would hold their own. They saw steadily rising wages and stability. These churches built gyms and had weekly Wednesday night meals because for 2 generations, they had the excess time, energy, and attention to do that sort of work.

What about poverty? Ask any proponent of capitalism and they’ll tell you that no greater force for lifting more people out of poverty exists. So in church the way to combat poverty centers on opportunity and education. Basically get people on their feet to compete in the marketplace and with enough hard work and discipline they’ll get out of poverty. For 10 years I’ve worked in churches and nonprofits with this as the model. I worked at an elementary school tutoring kids living in poverty. I worked at an after-school program mentoring middle schoolers. I lived in a Catholic Worker House with formerly homeless guys. I’ve seen it up close. I’ve volunteered in job skills training, shelters all of that stuff.

Here’s the thing that I find so frustrating: it doesn’t work. Don’t you hate that? Don’t you hate devoting time and energy to something that doesn’t work?

So how’s that story above, the one about capitalism and the working class and all that explain this better than the story of opportunity, job skills training, and education?

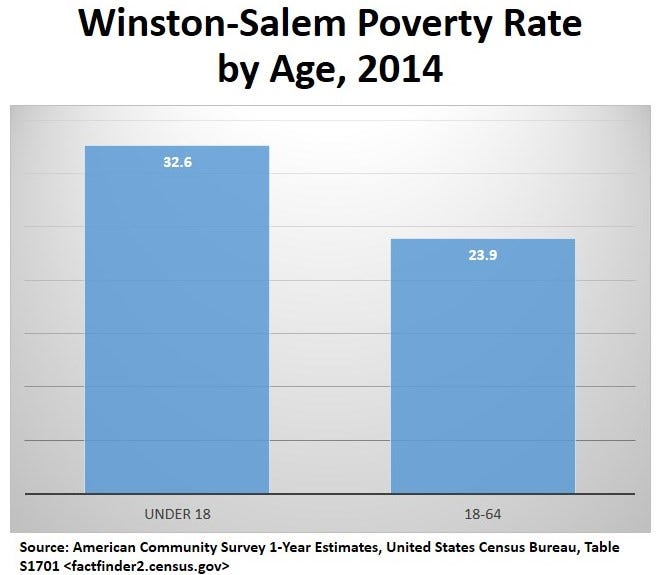

I used to work at a church in Winston-Salem in Forsyth County, NC. Like pretty much every county they realized they had a poverty problem and set out to look at what caused it and what to do about it. I noticed two really interesting charts they came up with from their study. The first just a slide on their website and the other in the final report. Here’s the first chart. Child poverty looks horrible. It’s a blight on the city and our country that so many kids live in poverty. It also appears fairly similar to adults living in poverty. And if you tend to think education, economic opportunity, and hard work solve poverty, you likely prescribe them to both children and adults.

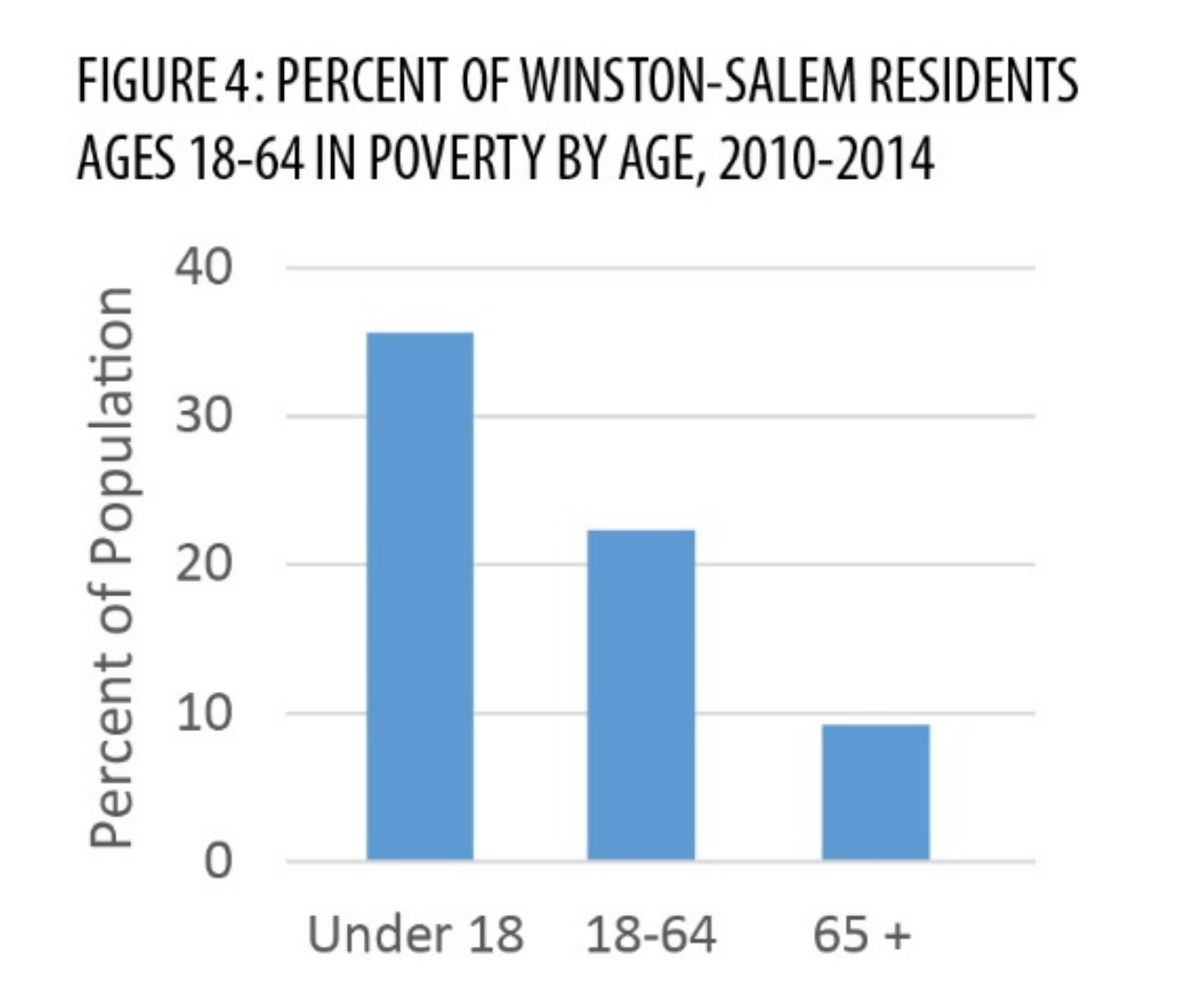

But the final report had a chart that tells a very different story.

Notice anything different? The poverty rate for adults 65+ drops significantly. So, you have to ask yourself, “What do people 65 years old and over do that they makes so much more money than kids do?” They must budget and work really hard and have a ton of economic opportunity. But have you ever met someone in their 70’s? Does that describe their life? Here’s the secret to lowering elderly poverty: Social Security. Before you introduce Social Security, the elderly poverty rate sits at 31%. After, it’s 11%.

Remember our story above, the one that explains things for us. Under capitalism, the profit gets divided between two groups: workers and owners. But what if you’re not a worker? Maybe you’re a child or an elderly person? Well you have to get income from somewhere else and for the elderly we’ve made significant strides with Social Security. We just don’t have anything like that for children (though SS does get several million children out of poverty every year).

So churches that devote time and energy to “economic opportunity” or tutoring or mentoring children as the way to alleviate poverty are going to get undermined by capitalism. I know a lot of good, well-intentioned people that have devoted themselves to helping children in poverty through tutoring, mentoring, and teaching. Here’s the really sick thing about capitalism: it makes a mockery of our best intentions. in the long run, capital wins. What’s worse is it makes you feel bad for not doing enough, not tutoring enough, not giving enough, not working enough.

I’m not saying all of this applies in every single situation or that it’s not incredibly complicated in the ways that it plays out. I’m also not saying that just explaining it can change it. But doesn’t it feel nice? Don’t you get frustrated wondering what’s happening in our world or churches and not having an adequate explanation?

Before I share what this looks like at our church, I’d like to share why it’s important. I think we all struggle to love one another. We struggle love each other because we have weak wills. We struggle to love each other because we lack perfect knowledge and others remain obscure to us know matter how we try to reveal ourselves to one another. With all of that, why would we want a system that has as its bedrock a fight, a struggle? The gospel says that against all our inclinations to believe otherwise we can live in love and unity with each other because God loves us. That’s the heart of the gospel as I understand it. The problem with capitalism beyond the practical, suffering of poverty and instability is the ways poverty and instability undermine our ability to love one another. It inherently sets us against one another. Our congregants leave work feeling pissed off and ripped off and it’s because they are ripped off. One of the co-pastors I work with once said the main marriage advice he gives is that maybe people aren’t pissed off at their partner, but at capitalism. I’d amend it and say, they should be pissed at capitalists.

Personally, all of this has saved my life in ministry. It’s made me attentive to so many more of the real, true problems I and my congregants face. It helps me understand that the best thing our church can do to help someone out of poverty is pay for the things they need to get out of poverty. It helps me explain what happens in the lives of my congregation in a way nothing else does. It also helps me understand the world towards which our church should work together: one in which we do away with this antagonistic relationship of capitalism.

Am I saying that naming this stuff will get droves of young people to your church? Of course not. A good explanation of these problems for ministry in 2019 doesn’t automatically translate into the power to fix them, but you can’t begin to imagine the solutions to these problems until you properly understand them, and I think understanding the work relationship in capitalism holds the key to beginning to unravel

I don’t think that eradicating capitalism with socialism will transform us into perfectly loving people. I just don’t think we can be more loving until it’s gone.

If you’d like to subscribe to this newsletter, you can do so here. If you want to follow me on twitter, click here. You can learn more about Jubilee Baptist Church here.