But it might work for us

In case you missed last week’s newsletter, I’m doing a 3 week series on a few things we plan to do as a church in the fall when we start as Jubilee Baptist Church. First we plan on hosting a Workers Anonymous group which you can read a bit about here. This week I will tell you a bit about our “Financial Literacy Course” and next week I’ll cover our project where we pay off people’s debts.

I spent this last week in Birmingham at the annual gathering of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, the “denomi-network” (I hate this term) of which my church claims partnership. While there I had dinner with a few other people that have either started a church in the last year or plan to in the upcoming one. I started talking to one guy about what we want to do at Jubilee specifically paying off $35,000 in people’s debts in the first year. He then raised the question of how we’d get to the root of the problem, people’s irresponsibility. “Money’s an emotional thing,” he told me, “people don’t approach it rationally.” He then went on to tell me about how he had worked three jobs right after seminary to pay of $30,000 of the over $100,000 he had in debt.

Pushing back a bit, I told him people don’t have a problem with irresponsibility so much as living under the power of an economy that requires them to go into debt, punishes them for it, and makes getting out all but impossible. I pointed out that while most people think they took out their own debt for an emergency or expanded opportunity (going to the hospital or the university) they also think that other people take out debt due to frivolous spending. I said that I just assumed We didn’t see eye to eye and about 15 minutes later I found myself arguing with not only him but two other pastors all claiming that they agreed with paying off debt but that doesn’t get to the root of the issue in the way that financial literacy classes do.

I’ve never actually taken a financial literacy class though I have gone to a sort of roughshod two day class for a grant I received. I wrote about the experience here. As I understand it, the typical financial literacy course consists in some basics in budgeting and saving, strategies for paying off debt, some lessons on compound interest and savings. I’ve also witnessed a strong motivational-speaker element to these courses. I have overheard Dave Ramsey enough to get his tough love schtick. I talked about him on a podcast recently and unfortunately they had to cut the part where I called him an asshole.

The conversation took an interesting turn as I kept returning to the fact most of the poor can’t work (“children, elderly, disabled people, and students make up around 70 percent of the poor”) and this should tell us something about our economy and what financial literacy can actually do to help people. It doesn’t help people to tell them that they can get themselves out of debt or that they bear responsibility for their financial situation when they don’t.

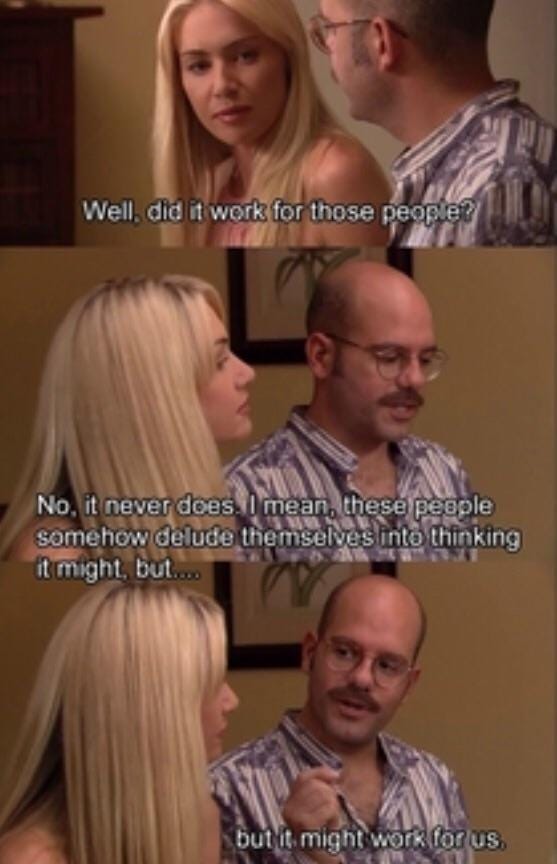

Eventually I realized our argument drifted to how to pastor, what we tell people facing the misery of poverty or the anxiety of financial insecurity. “Look, you can’t just tell people they can’t do anything! People still have agency! I would encourage you to think about how you can give them some hope. Even if financial counseling doesn’t work for most people [it doesn’t], it might work for them!” It felt as naive as Tobias Funke in the meme above. I just don’t find this a healthy way to pastor people. Any time a pastor offers advice on what someone should do with their agency in a situation, they need to have a reasonable and truthful accounting of that person’s agency to begin with. We can do a great deal of harm to one another by imagining someone possesses a power they don’t have, for example, the power over their financial situation by budgeting. As Louis Hyman says in his excellent book Borrow, “The danger of budgets, ultimately, is believing that they will tame not only you but the world around you.”

I think about all this from the perspective of needing to pastor people, of wanting to help them understand what it is they are going through.

And that’s where Jubilee Baptist’s financial literacy class comes in. At the moment a congregant and I are developing the class based on the very practical, real problems we see people running into. Stuff costs too much. They don’t make enough money. They work longer hours for less pay. Everyone has debt. Only a few can afford housing. These things get worse and worse the further removed you get from white men though they certainly persist as problems for plenty of them as well. Pastors have to answer for this. They have to tell people something to make sense of what they are currently going through.

So in our class, we move from those problems to even bigger questions. What is money? How did this economic system get started and why do we have it and not others? What central features make up “capitalism” and how do we understand how they effect our lives?

And for all of this, 19th century philosopher and Thought Leader, Karl Marx serves as our guide. This congregant will teach a class walking people through portions of Marx’s work, Capital, not because Marx answers every question and problem people have but because he answers some very fundamental questions, ones not answered as thoroughly or adequately anywhere else. So we plan to read Marx but also talk about why it matters and how it can help explain where people find themselves. We’ll do a kind of rock, paper, scissors meets the Hunger Games exercise to talk about how employment and wage labor work under a capitalist system of production. Of course, this kind of financial literacy as awareness of the systems that shape someones life stand in start contrast to the financial literacy that says people can and should get themselves out of debt by scrimping and saving. But one accords much better with reality, and I believe the former does not the latter.

Which brings me all the way back to the argument with the other pastors. The pastoral responsibility amounts to instructing and leading people to accord themselves together with a reality in which God is real and includes our material, historical world as we find it, fight it, succumb to it, are changed by it and change it. Any financial literacy class that starts from faulty premises of reality and an unreasonable account of the political-economy of capitalism will end up giving people a bad education and setting them on a path of failure. I do not care to set people on a path of failure. I have no interest in training people to see themselves as powerful if our society does not give them much power. I wish I could talk to the congregants of those other pastors. I wish I could tell them that they find themselves distressed because the powers and principalities of this world created and organized a system called capitalism and it seeks to rob, kill, and destroy and that I wish I believe it could be otherwise, but we’ll have to fight for it together.

As David Smail puts it, “Power is a social acquisition, not an individual property.” If our society doesn’t give someone much power, I won’t try to convince them they have it, at least not on our society’s terms. I hope that we help people move to acquire some social power together by studying primitive accumulation, commodities, wage-labor, and the working day. We’ll do that alongside paying off people’s debts and helping them organize unions. Might not amount to anything, but I’d rather fight reality as it is and lose than win in a delusional world that doesn’t actually exist.

I don’t know what it will mean for people to understand themselves as subjects of a capitalist system, a system with specific, historical workings that effect their lives, but I do know that telling them they have power that I don’t believe they do does them a disservice at best. Imagine confidently telling anyone that anything they do individually right now will make a difference. I can’t. Our only hope lies in collective action adequately accorded with the reality of the problems we face. My hope lies in the in collective ownership of the means of production and in a society that provides for everyone as they have need and asks only that they contribute what they’re able. At this point that you can accuse me of being as naive as Tobias Funke or that pastor that tells people they can get out of debt by budgeting better and making better decisions. I accept the accusation that I don’t know what I’m talking about and say the only thing I can in return: But it might work for us.

If you’d like to subscribe to this newsletter, you can do so here.

If you’d like to follow me on twitter, you can do so here.